On Air Now

Relaxing Evenings with Zeb Soanes 7pm - 10pm

19 July 2022, 16:54

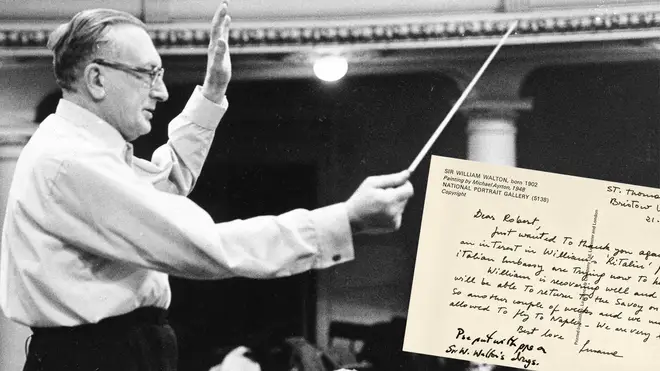

William Walton, composer of ‘Crown Imperial’, imported up to 2,000 prescription pills each year with the help of the Home Office, newly published documents reveal.

William Walton, the British composer behind the royal classical music favourites Crown Imperial and Orb and Sceptre, once enlisted the help of the Home Office to ‘illegally’ import prescription drugs to his home in Italy, according to new records released by the National Archives in Kew.

The documents, which have remained secret since they were created in the 1980s, reveal Walton’s dependency on the stimulant Ritalin, and his wife Lady Susana’s role in ensuring her husband could receive his prescription after the Italian government changed its laws restricting the use of the drug.

Ritalin is a prescription medicine and stimulant of the central nervous system, which consists of the brain and spinal cord.

While it isn’t known why Walton relied on the drug, Ritalin is most commonly prescribed today to treat ADHD, and, less commonly, narcolepsy. Walton’s prescription came from his Harley Street doctor, Michael Wilson, who stressed the importance that the composer had access to his “essential life-saving medication” in a testimony to officials.

Read more: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II’s contribution to classical music

Walton and his wife had moved to the Italian island of Ischia, just off the coast of Naples, in 1956. At the time, Ritalin was not a legal medication there, so Walton would collect up to 2,000 pills a year from Dr Wilson on trips to London, and take them back to Italy with him.

A spanner was thrown in the works in 1978, when the Home Office Drugs Branch informed Dr Wilson that his arrangement with the composer was, in fact, illegal. Instead, it was arranged for Walton to access his prescription through a legal loophole. Dr Wilson would write a year’s prescription of the drug, and authorities in Britain and Italy would issue one-off licenses to bypass laws against the export of controlled substances.

This all changed in 1982, when the Italian government legalised Ritalin, but didn’t make it available in the quantities the composer needed. The authorities on the receiving end of the supplies also said that the new law voided the import licenses, and that they could no longer accept deliveries of Walton’s prescription from the UK.

Recently turned 80, the composer was understandably in some distress. As the need for a new supply of the medication grew increasingly pressing, he enlisted the help of the UK government once again.

Lady Susana wrote to a police inspector friend to ask if he would send a year’s supply, despite knowing that granting her request would break the law. Instead, the inspector contacted the Cabinet Secretary Robert Armstrong.

Negotiations went back and forth between Downing Street and the Home Office, before Armstrong wrote to Italian ambassador Andrea Cagiati for assistance. Cagiati responded, saying it would be impossible to resume the import licenses as before but would see if he could pull any strings in Rome, to get Walton his prescription through the Italian healthcare system.

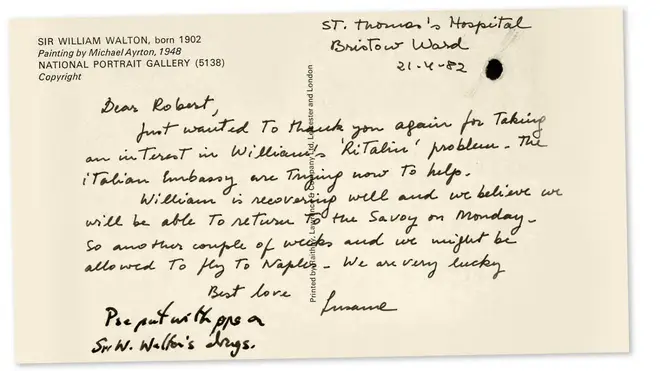

Lady Susana, on hearing this update from Sir Robert, replied with a handwritten postcard – featuring a portrait of William Walton at 46, no less – to enthusiastically thank him for his assistance:

“Dear Robert,

“Just wanted to thank you again for taking an interest in William’s ‘Ritalin’ problem. The Italian Embassy are trying now to help.

“William is recovering well and we believe we will be able to return to the Savoy on Monday. So another couple of weeks and we might be allowed to fly to Naples. We are very lucky.

“Best love, Susana.”

Addressed as being sent from the Bristow Ward of St Thomas’ Hospital in central London, this correspondence is the last known record, and the trail runs cold thereafter.

Sir William Walton died in his wife’s arms, at home in Ischia in 1983, a few weeks short of his 81st birthday. According to Lady Susana, the composer had been suffering from heart and lung problems for several months, and eventually died on the morning of 9 March from a lung haemorrhage.